A Moveable Feast of My Own

DaVinci, Hemingway, and learning to feel alive at 38

For the audio version, visit Substack.

"You belong to me and all Paris belongs to me and I belong to this notebook and this pencil."

-Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

Sunday, September 21, 2014 — Phoenix, Arizona

"There was so much to write. He had seen the world change; not just the events; though he had seen many of them and had watched the people, but he had seen the subtler change and he could remember how the people were at different times. He had been in it and he had watched it and it was his duty to write of it; but now he never would."

"I'm glad that you started writing so you won't feel that way when you die," I said as Guy closed the book. His eyes met mine from behind black frames.

"I won't feel anything because I'll be dead," he replied with a smirk, handing the book to me across his small high-top dining room table.

He suggested that I read The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway for inspiration. It was our second Sunday morning spent writing together, a scenario I hadn't imagined on our first Sunday morning a couple years prior, sitting in the passenger seat of his car. That morning he had driven me home after an evening typical of early 2000s Scottsdale, Arizona, where young, tanned $30k Millionaires ignored the economic crash in foggy nightclubs, lost in a haze of Sex, Drugs & EDM. Somewhere between that first meeting at 25 and this quiet morning at the age of 27, Guy, who had become a friend, introduced me to classic literature, a gift I didn't know I needed but somehow he did.

As I read, I realized that Guy and Hemingway weren't that dissimilar. It was another moment in which I wondered whether Guy was a product of his reading or if he and every other male on the planet inherently possessed some of the same traits, including a self-assured stoicism, providing a lens to perhaps depict life more closely to what it actually is.

"What is one thing you wish you knew about men?" he asked, as if reading my mind.

"If they really do lie," I replied, inspired by the main character of the short story. "If they're only saying what you want to hear for comfort's sake or if they really want to be with you."

"What do you wish you knew about girls?" I asked back. He gave three responses:

- Why they let men make them feel so inferior

- Why they hate each other so much

- Why women have a poor perception of themselves

"It probably seems as if girls hate each other because they're often jealous of one another," I explained. "Are guys jealous of each other, too?"

"No, they're not as jealous. They're more content," said Guy. "And competition is more of a sport."

"Content? You mean confident?"

"No, content."

"Are you content?" I asked.

"Yes, yes I am."

I couldn't fathom it, realizing that I was rarely content. And I had, perhaps mistakenly, associated content with complacent. But they're different.

Sunday, September 7, 2025 — Los Angeles, California

I am sitting in Venice Church before service. There is a certain anxiety felt from last night's surf date with Max who is a beautiful surfer boy, aeronautical engineer, DJ. I feel rejected which hurts. I want to come back to myself and to my power and joy. I am grateful to be here in Church this morning, and I am grateful for my upcoming trip to France. Lord, please help remind me of your chosen path for me and that you love me and craft an experience that helps me grow and shine.

The night before, I couldn't find the vaseline. Desperate times. And not for the exciting use case one might think.

"Why aren't we married yet???" His initial Hinge message had made me smile. Even if it was canned. Even if it was categorically love bombing. Even if it was directed towards a certain glamorized online persona that I wanted to believe I was but deep down knew was an illusion. To match it, the stray gray hairs desperately needed to disappear with the help of vaseline to protect my forehead so no traces of the dye could be detected. I finally found it as I ran around my apartment in a bikini. The one part of my appearance that seemed worthy of a casual surf date with a 25-year-old guy.

As I rode my bike to the beach, surfboard swaying on a newly installed yet quite janky rack, I thought, "I feel alive!" It was the feeling I had been seeking. The sensation of each cell being awakened out of the slumber caused by a dulling mixture of technology and isolation and middle age. Smiling, dreaming, hopeful. Old friends I once knew.

"Are you Annie?" I turned as I locked my bike against a post.

And it was over.

His cheekbones. His wetsuit. His smile. Why do guys have to be so much more attractive than their Hinge profile images while I was primping and spray tanning to remotely resemble mine? And how could he be doing so much more than I had at 25?

I was thrown off by his attractiveness and also nervous about my lack of surf skills. He knew I had taken five or six lessons, which should be enough to know the basics.

"For context," I told him as we stood at the shore, "I took golf lessons every summer in high school and had to relearn how to grip the club each time."

So there I was, re-learning the pop-up from this attractive guy and staring out into the sea unsure if I could face the choppy waves alongside him. He was patient though, watching me plop on the board like a chubby seal before guiding me into oncoming waves as he encouraged me to ride them on my stomach like a boogie board, a far cry from the surfer girl I wanted to show him I could be.

I encouraged him to go off into the waves to enjoy himself while I practiced, though I felt lost.

"Annie, move over this way!" he yelled, warning me about riptides by the rocks. I was happy to hear my name but also somehow felt like both a child and an elder at the same time.

I retreated to the sand to watch him ride the waves and stared up at the full moon, taking large inhales and exhales to capture that aliveness, though I couldn't escape the sinking feeling that became a reality when he returned to the shore. He stood instead of sitting beside me, clearly ready to be on his way, and then parted with the dreaded phrase, "Take care," which I had come to know as a phrase said by those you likely won't see again.

Despite the beauty of the sunset and full moon, tears were shed as I rode home out of disappointment for the cells that had stopped dancing. A fun experiment that I thought might help ignite and/or soothe my mind had backfired; I should have known I was too sensitive such risk. And now, I couldn’t help the feelings of excitement for this stranger and his life ahead. And almost none for my own.

I didn't know then though that the prayer would be answered. Even if the answer looked different than I imagined.

Sunday, September 14, 2025 — Paris, France

The trees and bushes looked the same as the trees and bushes in California and the Midwest and most places I'd been. I wondered if other people also expect foreign countries to look like other planets, or at least for the shrubs to appear different, as the Uber made its way from Paris Orly Airport to the city.

But just as the Queens Midtown Tunnel transports you into the concrete jungle of Manhattan before you can even begin to comprehend the microcosm you've entered, the entry into Paris proper happened before I could finish a last-minute Duolingo lesson.

The retail storefronts in the foreground with the looming view of bright centuries-old buildings towering with their unique architecture and floor-to-ceiling windows was breathtaking, almost too much to take in. Corner boulangeries with canopies and cursive fonts. An energy, a buzzing. Bicyclists and cars and pedestrians. Streets at odd angles, running in every direction, like its inhabitants: little ants adorned with the latest fashion, moving and living effortlessly and all at once.

An instant sense of the world-renowned romanticism without pinpointing exactly the cause or source. A question to answer, to take your time figuring out. Something to experience versus Google.

And I had made it, all alone, to the city on my 2025 Vision Board and the site of my favorite writers' and artists' creative inspiration. None of the past mattered. Except that I was here. Peering out the window like a small child in a car commercial, seeing Christmas lights or mountain ranges for the first time, already wondering where Hemingway walked.

The Uber dropped me in Montmartre where I carried my luggage up a seven-story walk-up. "14, 13, 12, 11…" I counted down in my head at each mini flight. Fortunately, the sight of the space upon opening the door rewarded me for my work. It was quirky and well-curated, the kind of space that is half-home, half-art piece. Skylights and plants and a bright red retro telephone and windows that opened to a busy street below with a view of Sacré-Cœur. Welcome to Paris.

"L'appartement est prêt! ❤️ You'll find some things in the fridge. Hope you enjoy the bubbly! À plus Annie!" my host, Julian, had messaged moments before. I opened the refrigerator to a chilled bottle of champagne and chocolates, a kind gesture. And exactly the treats I would have desired in the past.

For years, I'd told myself I'd have to drink again if I ever made it to Paris. The wine, the culture, the romance of it all. It was my favorite excuse, the one I'd use to justify starting again after periods of sobriety, and really any day. If I know that I'll drink then, then why not now? But I'd been alcohol-free for exactly one year now and planned to make it a year and one day. I ate the chocolates he left instead and thanked him. The champagne stayed in the fridge.

Before heading out into the city, I changed out of athleisure and into something more suitable for Paris. As I touched up my makeup, the light came into the bathroom at the same harsh angle as it had in the South of France over the past few days and momentarily brought back the same self-critical thoughts. The sideways light illuminated creases I hadn't noticed before, signs of aging that I had missed in Los Angeles, realizing it was the sight that the 25-year-old must have seen. All the evidence of my 38 years. How could I have thought he would find this beautiful?

But this time, just an hour flight away from the French Riviera, something already felt different.

Monday: DaVinci and the Shadows

"This painting is one of the earliest examples of naturalism with its three-quarter composition, lighting and shadows and display of intimate human connection," said my tour guide. "And perhaps where DaVinci drew inspiration for the realism shown in the Mona Lisa."

Domenico Ghirlandaio's painting of an old man and his grandson may have seemed ordinary, inconsequential and almost avoidable given its lack of beauty. However, standing in stark contrast to the "perfected" paintings of saints and holy figures with bright gold backgrounds we'd seen moments earlier from the 13th century, just before the Italian Renaissance, one started to understand the significance of being bold enough to paint humans as we are. Full of flaws.

"This profile portrait reflects the earlier Florentine convention for depicting women, always in strict profile," said the tour guide as we passed another pre-Renaissance piece. Women shown in profile were often idealized or symbolic. By contrast, three-quarter views, like in Old Man and His Grandson and Mona Lisa, were reserved for men or more psychologically complex subjects, because they introduced the sense of presence, personality, and mutual gaze.

And then we saw the portrait of DaVinci's boyfriend.

I'm not sure if I forgot this part of the 1990s art history tapes or if AP art in rural America left it out. But the picture was starting to come together. While many people believe Mona Lisa's notoriety is due to being stolen from the Louvre and returned, the true reasons seem much more in line with the Renaissance itself. One could imagine an intellectually curious male like DaVinci taking a stand to show the shadows, to give genders equal weight and to even infuse its subject with parts of his male lover, almost as a practical joke.

The tour guide mentioned DaVinci's tendency to leave things unfinished, a product of restless curiosity and perfectionism which kept him constantly moving between projects. It always made perfect sense to me though, especially since Leonardo da Vinci stands as the most famous example of a "Renaissance man," rooted in a belief that an individual could cultivate their abilities across a wide range of disciplines.

I thought of a boyfriend I'd once had who couldn't understand why I left things unfinished, especially as a finance bro who pays bills before they're due, never knew an overflowing laundry basket, and could eat a handful of granola as dessert. He saw potential in me but couldn't grasp what held me back. I couldn't explain it then. The way curiosity pulls me in a thousand directions, how my creative process relies on unpredictable, unforced moments, and the resistance that often grows closer to completion.

Standing before DaVinci's work, I wondered: What if that restless curiosity is exactly what made him a genius? New research claims DaVinci had an attention disorder. If he were alive today, he might be prescribed Vyvanse so he could focus on painting more Mona Lisas. But likely, that would have kept him from scientific explorations and statues and the many wonders of a curious mind. Why should he be judged by the "unfinished" when the scope of work deemed complete within a year of his life surpasses most of our lifetimes?

As our tour ended, I stood in line among the masses to see Mona Lisa up close. The crowd around me, full of body odor and ego, pushing and shoving to take cringy selfies of a painting they likely knew little about, was exactly the realism Ghirlandaio and DaVinci were trying to portray. Humanity's edges and oddities that are not always beautiful but make us who we are.

Tuesday: Picasso and Croissants

"Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life."

-Pablo Picasso

The Uber drove down narrow cobblestone streets in soft morning light. The city was in a quiet, sleepy state; normally so busy, but now like watching a small child sleep, a beautiful innocence. This new part of the world touched a part of my soul without me even fully knowing it.

I want more of this. I need it, I thought. Next year, I'm coming back to Europe for a month. The idea arrived as a lucid conviction as I exited the Uber and found the red door of 7 Rue de Béarn.

Ten minutes until class. I circled the block, imagining what life might look like if this were my normal Tuesday morning. Though, then, I likely wouldn't have the luxury of learning how to bake croissants with a group of retirees and honeymooners.

Four hours of thinking about nothing but rolling dough, folding butter, and gently sweeping off flour between the layers. The precision of this delicate pastry-making piqued all my senses, maybe from novelty, maybe from the tactile, thoughtful nature of it. No rush. The dust of everyday life, the long hours at a laptop and isolation, washing away with each fold of dough.

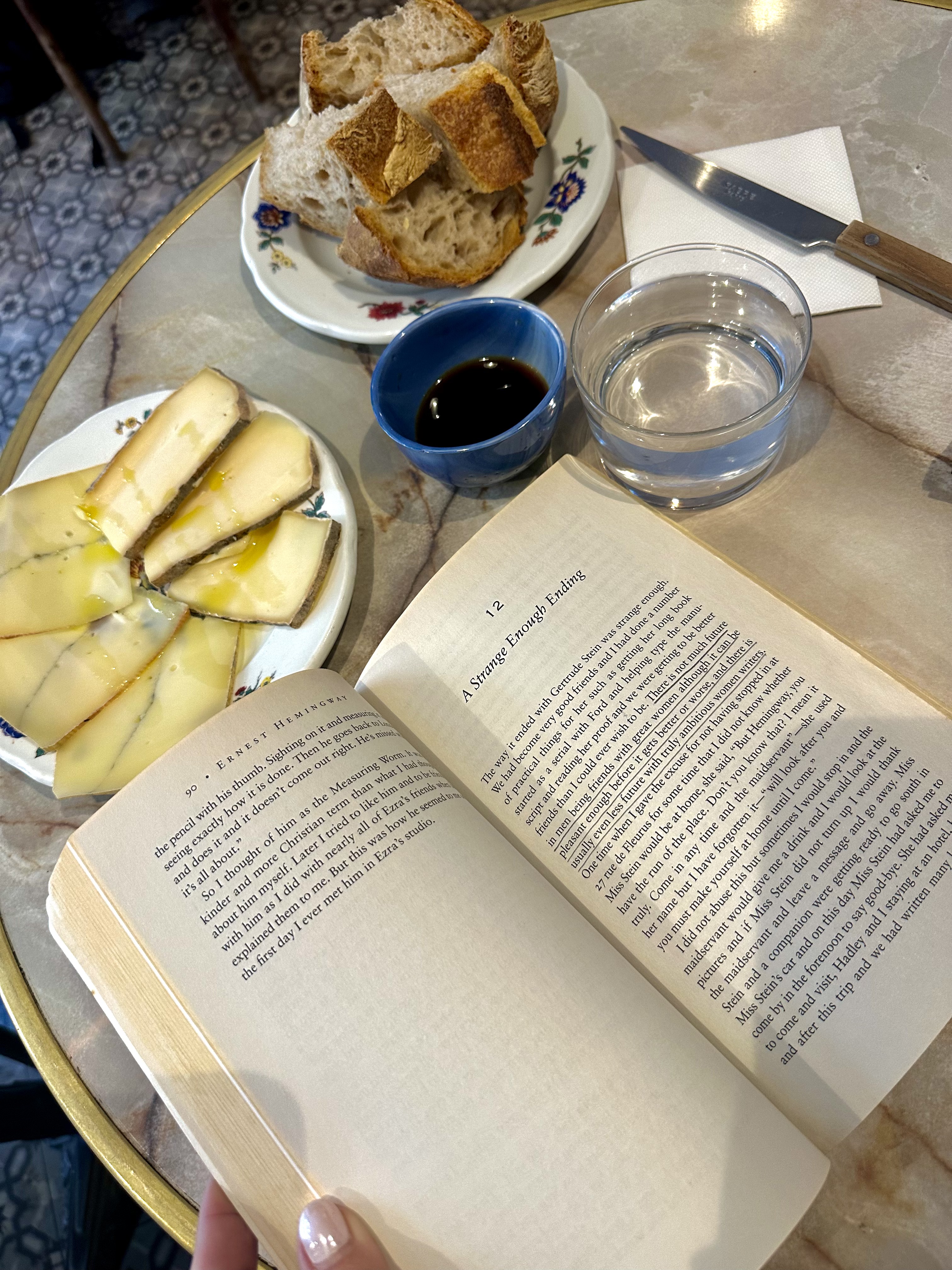

The butter-soaked bag filled with our creations sat next to me in a quaint café afterward, where the single employee stood in the street smoking between customers. I had the lunch of my dreams: cheese and bread and olive oil with bold espresso as I re-read about Hemingway's winters in the Alps. There was a freedom in eating exactly what I wanted to eat and reading exactly what I wanted to read, in a four-table café, no one knowing I was there, savoring the sensation.

After lunch, I walked to the Musée Picasso for a self-guided audio tour that moved me through rooms chronicling his artistic evolution: Blue Period melancholy, Rose Period warmth, the African-inspired masks, Cubism and the collages, and back again to something almost classical. A man who never stopped exploring, never stopped asking questions.

In another room, towards the end of the exhibit, a collection of portraits stopped me. His lovers: Dora Maar and Marie-Thérèse Walter. Faces rendered in bold lines, asymmetrical features, eyes at different heights.

The portrait of Dora Maar caught my attention most. Something about her reminded me of myself. The dark hair, yes. But more than that, it was the prominent nose, like my original nose, the one I'd obsessed over for so many of my formative years, seen as a flaw that needed fixing.

And here was Picasso, painting it as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

A placard on the wall read: "What is a face, really?" asked Picasso in 1946. "That which is in front? Inside? Behind? And the rest? Doesn't everyone look at himself in his own particular way?"

The quote struck me because it articulated the question I'd long considered as an aspiring portrait artist, fascinated by the intricacies of faces, trying to capture exactly what I saw. I've spent my creative life trying to make my paintings more and more real. And here was Picasso, who had started as a skilled realist and then spent his life moving in the opposite direction.

Standing in front of Dora Maar, I thought about another Sunday morning with Guy eleven years earlier. I'd told him all my insecurities about my looks. How I felt outwardly masculine when inside I felt feminine, how I'd gotten a nose job to try to fix the mismatch. But it still existed.

"If you want to be perfect, let yourself be imperfect," he'd said, quoting a Tao teaching. And he went on to provide two potential perspectives. One framing: I'm going to find myself beautiful despite what society thinks, still giving society's opinion weight, still fighting against an external standard. The other framing: I don't care what society thinks. I'm beautiful, the impossible-feeling choice, like something other people could access but not me.

I'd later learn that Picasso psychologically tormented Dora Maar during the years he kept dual relationships with both her and Marie-Thérèse. That even though she was a successful surrealist artist in her own right, she suffered mental breakdowns because of him. Their relationship was one of many he destroyed. It complicated my feelings on his work, knowing the man who painted her face also crushed her spirit. Genius and shadow. Muse and misogyny. Creativity and vice.

But Dora Maar's face still spoke to me across the decades. Woman to woman. Artist to artist. Without knowing her, I knew her face was only a fraction of her being, only what was in front. Inside, behind, and the rest remained hers alone.

I still couldn't say I was totally fine with my appearance, including the lines across my face I'd discovered in the fall light of France. The insecurities hadn't vanished. But something was subtly shifting. Maybe I didn't need to arrive at "I'm beautiful" today. Maybe it was enough to stand in front of this portrait and feel a little more seen. A quiet acceptance building as the dust of everyday life shook loose.

Wednesday: Hemingway and 27 Rue de Fleurus

"Could we maybe not do the acting part?" I interjected mid-dialogue as we sat in Luxembourg Gardens, just me and the tour guide, looking out at the iconic fountain. "And maybe just chat about Hemingway instead?"

I immediately didn't like him. Maybe I had made up my mind before meeting my tour guide, but his curt greeting and garlic breath sealed the deal. It was partially my fault for booking an actor-led tour when I knew that someone cosplaying Hemingway would creep me out. But somewhere along our brisk walk from La Closerie des Lilas back to the Gardens, I decided to let it go.

"Where are you from?" the guide asked after we'd settled into just talking.

"California but I grew up in Illinois."

He assumed this was why I was interested in Hemingway. A shared geographical upbringing. Along with a hunting hobby.

"I used to have a blog," I said. "And a friend introduced me to Fitzgerald and Hemingway. My writing used to be like Fitzgerald's, a lot of adjectives and overly wordy. But I appreciated Hemingway's more concise language."

And without anyone asking, I went on.

"And it's clear that both of them struggled with drinking, along with Zelda Fitzgerald. I also struggle with drinking even though I've given it up now. As a writer, I can understand how creatives can struggle with substance abuse. I also struggle to write without it. And so I guess that part of their story always resonated with me, too."

I thought back to the weekend before, on the eve of my one-year alcohol-free anniversary, on a yacht in the Mediterranean, looking out at Monte Carlo. All of my friends dancing and free. And I stood there frozen, leaning against the railing, wondering why I couldn't let go without alcohol, wondering if I'd always be this way, fearful of what that meant for my fate. The girl once known as the most fun wedding guest, now potentially the most boring. How would I ever be someone's date? I thought about The Great Gatsby lifestyle that the Fitzgeralds had emulated and that had once made me feel so alive: flowing champagne at a party where anything could happen.

But I'd made it through. And here I was in Paris, the city of wine, drinking sparkling water at cafés and feeling more alive than I had in years.

My tour guide led me back through the Luxembourg Gardens, and I learned he was from Belgium. Had worked in restaurants. Was living the struggling actor life in Paris, taking on odd jobs like this one. The artist life, really. Not so different from Hemingway himself, or the many who had come to this city before him, hungry for something more than food.

We strolled past the Medici Fountain again, past the pathways Hemingway had wandered nearly a hundred years before. He wrote about being hungry in Paris, skipping meals when he'd given up journalism and was writing nothing that anyone in America would buy. How he'd walk through these gardens to avoid the bakery windows and the people eating at sidewalk tables. How he'd go into the Luxembourg museum and find the paintings heightened and clearer when he was slightly starved. How he learned to understand Cézanne better when he was hungry, wondering if Cézanne had been hungry too when he painted.

I was grateful to be walking these same paths satiated by protein yogurt and pastries. I'd tried the starving artist life when I first arrived in LA, nearly going hungry out of my own bad decisions while trying to prioritize creativity, and learned the hard way that it wasn't sustainable. But I could imagine what it was like for Hemingway, stomach empty, finding sustenance in the Cézannes when there wasn’t any bread.

Upon my request, the tour ended at a narrow street with tall buildings. 27 Rue de Fleurus. Gertrude Stein's home, where the Lost Generation had gathered: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Picasso, Ezra Pound. Americans and artists in Paris together, influencing each other, paintings inspiring novels inspiring poems. I had pictured something grander, a Carrie Bradshaw stoop perhaps. But here was just a door, a plaque, a quiet street.

Standing there, I couldn't help but think about Guy and how we had dreamed of something like what Gertrude created: our own artist community in Barcelona. We'd settled for Sundays spent writing together in the meantime. Though I love America, I could understand the pull of that bohemian expat life, the appeal of leaving everything behind to find your people in a city that didn't care who you were before.

The tour guide took my picture in front of the door. I thanked him and we parted ways.

I wandered the neighborhood alone afterward, in search of an espresso, and that's when it started to feel real. Bookstores on every corner. The literary hub I had imagined. I sat at a café with my espresso, watching the street, and finished re-reading the final pages of A Moveable Feast: "I would not forget about the writing. That was what I was born to do and had done and would do again."

Thursday: Van Gogh and Valadon

Julian knew what he was doing with the placement of the large trendy mirror propped against the wall with impeccable lighting from the skylights overhead. I admired myself in the light linen pinstriped two-piece set, meant for Venice Beach or the South of France, but which also belonged to the beauty of a warm day in Paris with no validation needed but my own, making it perfect simply because I deemed it to be. I smiled at myself in the mirror, thinking of where I was headed: a rooftop restaurant named Maggie's. A suggestion made by Julian, another wise choice on his part.

Often when we're met with endless possibilities, self-doubt trumps gut instinct, which I feared was the case as I entered Maggie's, any table a potential option on an empty Thursday. But my intuition didn't lead me wrong as I sat at a table tucked into a corner with a view of the Eiffel Tower in the distance to my left. If peace wasn't picturesque solitude, bright purple grilled octopus, toasted bread, and sparkling water, I don't know what is.

However, this quiet bliss was broken by intrusive, very American panicking: Where is the waiter with the check? I wish they took tips in Europe because maybe then I wouldn't potentially be late for my Montmartre tour!

But soon enough I gathered with a group of strangers from around the world for the last time this trip as we set off to explore the culture and art history of what I call the Brooklyn of Paris: Montmartre. The artistic, rebellious neighborhood that has since been gentrified, but where a certain grit remains that attracts those who appreciate the avant-garde and lingering authenticity.

We started at the Moulin Rouge. Though the site piqued my interest more than anticipated, I was ready to move on to the less touristy and more art-related. But what I would find is that the two were intertwined, at least when it came to Van Gogh, an unexpected surprise.

As I stared at the blue door of 54 Rue Lepic where Van Gogh resided with his brother Theo from 1886 to 1888, I thought about the unread book sitting on the bookshelf above my bed back in Venice called Touched with Fire. When frequently faced with the battle to regulate intense emotions, I often hypothesized about the potential connection between creativity, sensitivity, and mental health. It was during one of these depressed moments that I purchased the book with the subtitle "Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament," with Van Gogh as a core subject.

The tour guide told us details of his life that questioned parts of his notoriety. Van Gogh's ear, for example. We don't actually know if he cut it off himself or if it happened some other, more innocent, way. What we do know is that he had the audacity to hand it to a dancer at the Moulin Rouge down the street, a detail so absurd it could almost be categorized as comedic genius. And his death, too, remains a mystery. Some say he shot himself; others believe he was shot by a teenager who had been taunting him. But what we know for certain is how much art meant to him. He may have been touched with fire, but he painted through it all: through the poverty, through the ear and the asylum and whatever really happened at the end.

But it wasn't just Van Gogh's story that stayed with me from that tour. It was also a lesser known female artist: Suzanne Valadon.

A Montmartre native, Valadon started as a muse and model for artists like Renoir. She silently learned their ways through watching, through posing, through paying attention. And then she became an artist herself. Edgar Degas was her first buyer. "That day," she said, "I had wings."

She painted harsh but honest images of people from her everyday life. She didn't find suburban life or traditional norms right for her, even when she tried. She preferred her younger beau and supported a struggling son, helping him find his way through painting as well. Valadon wasn't a Realist, a Fauvist, or an Expressionist. She simply painted what she knew. Perhaps she wasn't touched by fire, but was the fire. A fire that spread and paved the way for other women artists, in Montmartre and otherwise, to live their own way.

Friday: Saying Goodbye and À Bientôt

In the fresh morning air, I happily navigated the nearby streets without Google Maps on a quest for my last éclair, last espresso, and some mementos. Postcards from a local father-son lithography shop, prints by a local female artist, and a small suede red belt, well-worn and vintage. A gift for myself.

On my way back, I climbed the steps of the Sacré-Cœur again to look out once more over Paris, taking in the view. In the short time I was there, a subconscious question kept repeating itself: What is it about Paris that both soothes and ignites the artist's mind?

My friend Elizabeth had told me before I left that she sensed something ancient in me that Paris might activate. Codes in the air, in the land, in the exchanges. "Like the Renaissance," she'd said, "you’re in the birthing canal." I hadn't fully understood what she meant. But standing there, surrounded by the ghosts of artists who had come to this place seeking inspiration and found it in rich history, a vibrant pulse, a portal to innovative self-expression, I felt it. Something ancient recognizing itself. The pull of a lineage I felt like I belonged to, coupled with a renewed desire to make the creative fire worth it: to use its light and energy to create rather than allow self-destruction.

And ironically, or perhaps unironically, the ride to the airport later that day was void of the heavy emotions that typically accompany me when leaving a place. There was no rush or overwhelm or crying or regrets. There was just, dare I say, a sense of contentment.

Before Paris, I started believing that feeling alive meant cells dancing just because of a male's attention, a stranger's text, a sunset shared. But Paris reminded me the cells could dance on their own: in a museum, on cobblestone streets, in front of a mirror with no one watching. The aliveness I'd been seeking wasn't waiting just on the beach at home. It was waiting in me and in the call to a little more adventure.

Sunday, November 30, 2025 — Los Angeles, California

The Sunday that followed would have been a lovely way to end this personal essay. After a day's rest, I found myself sitting in a French restaurant in Los Feliz with my brother and sister-in-law, telling them about my trip over macarons, feeling quite beautiful in Levi’s paired with the little red suede vintage belt. We stopped to smell the flowers at the corner stand, similar to the flower stands in Paris, on our way to a film screening of Greta Gerwig's quirky indie film, Frances Ha. With a fresh perspective, the Sunday scaries were nowhere to be found; it all felt perfect. Maybe this was the new Parisian Annie.

But that would be like a portrait painting without shadows or creativity without a vice.

In the weeks that followed that Sunday, there was a panic attack after working long hours to "catch up," and then many mini existential crises mixed with a deep sense of loneliness while at the same time a longing for the freedom of anonymity. I became angry with myself that I had lost the woman who nearly skipped down the street with a bag full of fresh croissants on her way to a museum, daydreaming of fashion and art and plans to spend a month next year in Barcelona, a quick hop to Paris.

Knowing that reality television and compulsive Pinterest scrolling would not return me to her, I signed up for Elizabeth's Artist's Way group again, which had reconnected me with painting and poetry and life outside my apartment this time last year. The program is rooted in the idea that creativity is a spiritual practice, that God gives us gifts and calls us to use them, that isolation and stagnation is where the enemy wants us but connection and creation are where we come alive. And now in Week 3, it is bringing me home once more, like the birthing canal she referenced before my trip.

Hemingway's novel that led me to Paris is named A Moveable Feast because the memories, joys, and experiences of his time in Paris as a young, struggling writer would always stay with him. It suggests that a happy, rich experience, similar to fleeting moments of contentment, is not confined to a specific time and place but becomes an internal feast that can be carried with you always, regardless of your circumstances.

And that is why, despite the fire that burns in my mind and heart in so many different creative directions, I felt it my duty to write - and complete - this Paris piece. As well as, in time, more stories of Guy’s on Sundays, a coming-of-age tale, because perhaps we all are always coming of age.

Maybe that's what faith is too: trusting that the fire was given for a reason even if it sometimes burns, that the calling is meant to exceed our ability, that we were never supposed to do it alone.